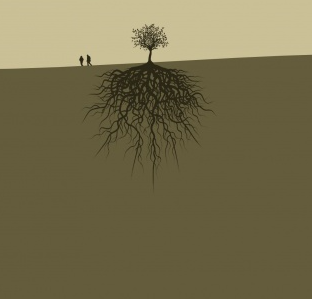

the dry season

It took over a decade, and more than three years of construction, to build the Hospital of Hope, which just opened its doors in March 2015. The hospital is inside a walled compound, and contains an outpatient clinic, the hospital itself, six houses, five guest rooms, a recreation/dining room, a pool, a maintenance shed and a water tower. The perimeter measures exactly one mile. The wall that surrounds the compound is only about four feet tall -- it was built to keep poisonous snakes out, not people. In addition to building buildings, the construction team also planted a lot of new trees that will eventually provide shade during the dry season, where the temperatures soar to 120 degrees or more.

I was talking to one of the groundskeepers, and he told me there's a trick to planting trees in northern Togo, where the dry season is three times as long as the rainy season, and temperatures soar to over 120 degrees.

When you first plant a sapling, he said, you give it less water than it needs.

"Why?" I asked. "Won't that kill all the trees?"

He shook his head. "You give it water, just not quite enough water. Because it makes their roots grow deep."

I was thinking about his words, and about heresickness, which I wrote about last week. Thinking about the times in our lives when we are forced to stay in difficult situations. The times when we can't get away from pain, so we have to figure out how to endure it. How to breathe. How to stay.

When I look back on my life, the most difficult thing I've gone through was seven months of chemo and radiation for breast cancer. I've never felt so nauseated or exhausted, and have never been in so much pain, as those seven months.

People used to tell me, "This is going to make you a very strong person," and I wanted to kick them. Because becoming a strong person didn't sound appealing to me at all. The only benefit of getting stronger is so that the NEXT time something goes wrong, it doesn't hurt me quite as much.

And I didn't want there to be a next time.

As I've been thinking about Togo saplings, I've remembered times in my life where it felt like I was in a spiritual drought, where God seemed far away, and it felt like he was punishing me or ignoring me, because he didn't give me what I thought I needed.

And I see now that in those times, God wasn't ignoring me, and he wasn't a drill sergeant giving me a stiff upper lip so I didn't cry next time life was hard.

God was the still, quiet water underneath it all, and God was calling me deeper. Giving me less water on the surface so my parched roots would keep going, keep growing, keep searching, until they were anchored in him.

In the short run, it is painful and it feels like punishment, and we have nothing to show for our struggle. No visible progress, no obvious growth, no enviable fruit.

But in the long run, having deep roots means that our tree can grow to be healthy and strong. It means that we can produce quality fruit that nourishes other people, provide expansive shade for other saplings who are just learning to grow, withstand storms of life that inevitably come and be revived by the Living Water.

The gift of heresickness, the gift of the dry seasons in our life, is that in these times, we become secure, anchored, deep people.

Because we got nothing that we wanted.

And everything we needed.